Teenagers these days have almost limitless sources for finding new music: legal services like iTunes or Amazon MP3, illicit services like FrostWire or Bittorrent, social networking sites like MySpace and Facebook, music blogs, band websites, YouTube, music videos on demand and music channels from their cable provider, satellite radio… even “old fashioned” technology like MTV. It seems that the original “information superhighway” – terrestrial radio – has been all but forgotten these days.

But back in the 50s and 60s, AM radio was the Internet. Teens relied on their radios to bring them the latest music from faraway places like Liverpool, England or Memphis, Tennessee. Music began to bloom everywhere like wildflowers. Entire genres of music, like soul and R&B, were exposed to mainstream white audiences for the first time. And no single radio station and no single DJ did more to help spread the gospel than XERF and Wolfman Jack.

To understand how XERF and Wolfman Jack changed the world, we unfortunately have to start with science and politics.

Below is a sample of a radio wave:

FM radio works by modulating the frequency of the radio wave (hence, FM = “frequency modulation”). The peaks and troughs of the radio wave get closer together or farther apart, depending on what’s being broadcast. In other words, you could stretch the right and left edges of the above picture (or squeeze them together) to “see” what an FM wave would look like. FM radio waves are short and cannot travel very far, nor can they penetrate tall buildings or mountains. This is why you lose an FM station when you enter a tunnel, for instance.

AM radio, by contrast, works by modulating the amplitude of the radio wave (hence, AM = “amplitude modulation”). With AM, the peaks get higher or lower, depending on what’s being broadcast. So you could take the image above and stretch the top and bottom sides (or squeeze them together) to “see” an AM wave. Unlike FM, AM waves are very long, and can easily pass through buildings or mountains. In fact, AM waves are so long that they can bounce off the earth’s ionosphere at night and travel in all sorts of directions. If you’ve ever listened to a nighttime call-in show on a local talk radio station, you might have heard people calling in from several states over. This is because the radio waves are bouncing off the ionosphere and landing hundreds of miles away. But more on that later.

In the early part of the 20th century, the United States, being an industrial giant, took a commanding “lead” in the number of radio stations it had versus Canada and Mexico. For this reason – as well as the usual American arrogance – when it came time to pass the North American Radio Broadcasting Agreement in 1941, the US had made into law what had already been practiced for two decades: a huge chunk of the available airwaves went to the US. Canada received the lion’s share of the remaining bandwidth, and Mexico received… next to nothing. The Mexican government, miffed at being snubbed by the Yanquis, decided to fight back by allowing their radio stations to broadcast at up to 500,000 watts, although most stations drew the line at 250,000. This was several times the power of any American radio station, which were limited to 50,000 watts by the FCC.

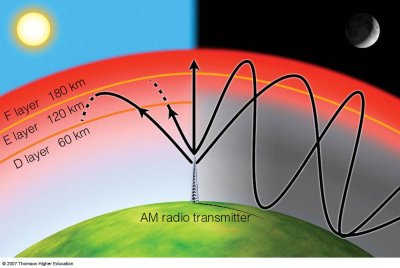

The difference between the wattages is important. The ionosphere is composed of three layers: the D, E, and F layers. The D layer, which starts around 53 miles above the ground, is ionized by solar radiation. During the day, the D layer absorbs AM radio waves, which physically limits the distance a radio station can broadcast. At night, however, the lack of solar radiation means that D layer essentially disappears. Radio waves that would normally be absorbed by the D layer are free to bounce around the atmosphere:

For this reason, the FCC requires most AM stations to reduce their wattage at night; if the stations didn’t do this, the nighttime AM dial would be an anarchy of different stations from all over the country “bleeding” in to one another. If your favorite AM station broadcasts locally at 640 kHz, without the “nighttime powerdown”, you could pick up stations all over the United States broadcasting at the same frequency. The FCC does allow a handful of stations – usually one in each of the larger markets – to maintain their full 50,000 watts at night. These are called “clear channel” stations, and they can often be heard hundreds, or even thousands of miles away. WBT in Charlotte, North Carolina and WSB in Atlanta, Georgia are both “clear channel” stations, which should not be confused with stations owned by Clear Channel Communications, a company that was originally formed to purchase WOAI, a clear channel station in San Antonio, Texas.

Mexico either didn’t have rules about powering down at night, or else made it exceptionally easy to obtain clear channel status. Due to the lack of a “power down” requirement, and the fact that the Mexican government allowed stations to operate at up to 500,000 watts, several radio stations sprang up on the US-Mexican border. These stations were called “border blasters” and at nighttime their programming could be heard across a huge chunk of the United States. In fact, on a clear evening they could be heard almost anywhere in the US, save for extreme portions of the American northeast or northwest.

The most famous of the border blasters was XERF, a 250,000 watt station located in Villa Acuña, Mexico. Originally given the call letters XER, the station was created in 1931 by one of history’s greatest oddballs: an American “doctor” called John R. Brinkley. Brinkley, born in 1885, attended several unaccredited medical schools, eventually obtaining his M.D. from the Eclectic Medical University of Kansas City (“eclectic medicine” was a direct ancestor to today’s “New Age” or “alternative medicine”). In 1918, Brinkley began performing a bizarre form of surgery: implanting the testicular glands of goats in his male patients as a type of erectile dysfunction therapy. The surgery (which cost $750 then, or around $7500 today) was, of course, completely pointless and had no effect whatsoever on the unwitting victims… of which, there were around 16,000.

Since erectile dysfunction surgery is elective, Brinkley had to travel from town to town, selling his “procedure” like the traveling snake-oil salesman he was. While in Los Angeles promoting his “cure”, he toured the studios of radio station KHJ. Instantly seeing how radio could be a sales tool, Brinkley quickly amassed the capital to create KFKB, the first radio station in Kansas. The station featured live music (sponsored by Brinkley, of course) and medical “write-in” shows, where Brinkley would answer questions mailed in by listeners. Brinkley “extended his brand” by organizing a group of affiliates to rebroadcast his show, and (in an act of breathtaking hubris), Brinkley would often prescribe medicine over the air using a “code” that the listener would take to a local pharmacy – which would then send a portion of the sale to Brinkley as a kickback.

As you might guess, none of this went down well with the medical establishment. Brinkley came under further fire in the late 20s when the Kansas City Star, which owned a radio station that competed directly with Brinkley’s, ran an exposé on the good doctor. By 1930, the establishment began to freeze him out: his medical license was revoked in that year, and later that same year the Federal Radio Commission refused to renew his radio license. Brinkley wouldn’t go out without a fight, however. In 1930, he ran for governor of Kansas; although he was off the air by that time, enough people knew him thanks to his radio show that he was able to get 183,278 votes (29.5% of the vote). Unfortunately, this wasn’t enough, and so he lost. He ran again in 1932 as an independent, losing again with 244,607 votes (30.6% of the vote).

Down, but not out, Brinkley traveled to the border town of Del Rio, Texas. There, he convinced the Mexican government to grant him a radio license, which they did in 1931. XER, broadcasting at 75,000 watts, quickly went on the air, and Brinkley began his quest for the Kansas governorship anew, all the while selling questionable medicines for erectile dysfunction.

When Brinkley heard that WLW in Cincinnati was operating an experimental AM station with 500,000 watts, he applied to the Mexican government for a new license. The Mexican government, fed up with being ignored by Washington over the issue of US radio signals “leaking” into Mexico, happily granted the request under the call sign XERA. Brinkley then had RCA, who had constructed the equipment in Cincinnati, build a similar station in Mexico. The station was easily picked up in Canada, and the radio waves crossed the north pole into Russia so regularly it’s rumored that the KGB used XERA broadcasts to train agents in American English.

The final nail in Brinkley’s coffin came in 1939. Already unpopular with the government for his quack cures and questionable medical ethics, Brinkley allowed Nazi sympathizers to broadcast on XERA in the run-up to WWII. And although XERA’s transmitters were located in Mexico, most of Brinkley’s actual broadcasting was done in Kansas over a phone line to the transmitter. Congress, with uncharacteristic speed, passed the Brinkley Act in 1939, which prohibited American-owned radio stations from broadcasting using transmitters based in foreign countries. Brinkley was therefore forced out of the radio business. The Mexican government confiscated XERA’s equipment later that same year. Lawsuits from former patients and investigations by the IRS led the formerly wealthy Brinkley to declare bankruptcy on January 31, 1941. Three heart attacks quickly followed, and one of Brinkley’s legs was amputated for poor circulation. He died penniless in San Antonio in 1942.

Amusingly, a man named Wilbert Lee (“Pappy”) O’Daniel would also use a border blaster in his own run for office, in this case for the governorship of Texas. O’Daniel spent much of his life in the flour business. He bounced around flour mills in the Midwest and South until 1925, when he moved to Fort Worth to take on the job of sales manager for Burrus Mills. There, he learned about the border blaster stations, and took a “hands-on” approach to advertising the brand on the radio. He wrote songs, gave on-air talks, and even formed a “house band” called the Light Crust Doughboys, who are still around today. When he considered running for governor, he asked listeners what they thought; O’Daniel claimed that 44,000 people wrote in and begged him to run for office. He did, and won two terms as governor. In 1941, O’Daniel ran for the US Senate against Lyndon Baines Johnson and also won, becoming the only person to ever defeat LBJ in an election. The character Menelaus “Pappy” O’Daniel as governor of Mississippi in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? is loosely based on O’Daniel.

XERA, confiscated from Brinkley, remained silent until 1947, when a man named Ramon D. Bosquez purchased the equipment and started broadcasting again under the call sign XERF. For the next 12 years, the 75,000 watt station’s programming consisted of shows by evangelical preachers, live music heavily sponsored by companies, and infomercials for medical products of all kinds. Essentially, whoever showed up at XERF’s studios with enough money could broadcast almost anything they wanted. And the station was about as exciting as a local-access cable channel.

That changed in 1959, when an attorney named Arturo Gonzalez convinced Bosquez to form a Texas corporation called Inter-American Radio Advertising, Inc., which would be based out of Del Rio, Texas. This would allow them to skirt the Brinkley Act and broadcast at their full power: 250,000 watts. The increased wattage allowed the station to reach far more listeners, and thus charge the preachers and advertisers more money. But it also had some rather interesting local affects.

Former XERF employees swear that on a humid night, not only could you see the electricity arcing on the tower, you could actually hear the voices of the broadcasters in the arc. You could hold a neon tube close to the tower and it would glow. You could park your car close to the tower and the lights would stay on. Grass and trees wouldn’t grow in the area, and birds apparently either avoided the area or dropped dead once they got too close to the tower. Whether this is true or not, I don’t know. But it sure makes for great stories that illustrate how powerful XERF was.

* * *

Bob Smith was born in Brooklyn on January 21, 1938. Bob had a lonely childhood, neglected by his parents and shunned by kids in the neighborhood. Bob was fascinated by radio, especially border stations like XERF. He’d spend hours listening to the preachers on XERF, not so much for their religious message, but for the spectacular showmanship they possessed. When Smith heard DJ Alan Freed – the broadcaster best known for bringing “black music” to a white audience – Smith knew exactly what he wanted to do. He moved to Alexandria, Virginia, where he attended the National Academy of Broadcasting. After graduating in 1960, he received his FCC license and got his first gig at WYOU in Newport News, Virginia. There he was known as “Daddy Jules”.

Despite his early success, Smith kept tuning in to the border stations. At the time, there was just something magical about them. Part of it was the fact that they were heard all across the country. A gig on a border blaster would guarantee national exposure. But there was more than just that. There was a… romance about the border. A place that was neither American or Mexican, but a strange mix of the two. There was a sense that laws were loosely enforced and outlaws and scalawags gathered there. Just as people once looked to the Old West for adventure, so people of Smith’s time looked to the border for the exotic and usual.

Smith just couldn’t resist the call of the border blasters, so in 1962 he moved to KCIJ, a tiny station in Shreveport, Louisiana, to be closer to the border. There he became known as “Big Smith with the Records”, and he further honed his skills at not just spinning records, but selling products during his show. He wouldn’t spend a long time in Shreveport, however. In less than a year, Smith took off again… but not before allegedly draining all of KCIJ’s bank account.

Smith hightailed it to Del Rio, where he used KCIJ’s money to act like a bigwig in town, handing out 5, 10 or even 20 dollar bills as if they were penny candy. Smith’s arrival was already the buzz of the town when he arranged a meeting between himself and XERF’s owners. Although they didn’t quite know what to think of this crazy gringo with the Beatle boots and a jet black pompadour, they nevertheless loved his money.

At 6:00 pm that very night, Smith went on the air as “Wolfman Jack”. Instead of an infomercial or ranting preacher, listeners that evening were treated to a gravel-voiced madman of uncertain background who played music from almost any genre and could sell ice to Eskimos.

Wolfman Jack was absolutely mysterious. Listeners didn’t know if he was black, white or Mexican. Whereas most radio DJs of the day droned on and on in sleep-inducing monotones, Wolfman Jack had a big, booming voice, accompanied by his trademark growls, howls and racy innuendo. People didn’t know if he was insane, or if it was all just an act. You could listen to Wolfman Jack and imagine almost anything you wanted to about him. Was he a crazy man, broadcasting in a straitjacket? Was he an outlaw that was drinking whiskey, smoking marijuana and sleeping with the chicas during the songs? You just didn’t know, and that was the Wolfman’s appeal… well, that and the truly vast selection of music that the Wolfman played every night. The Wolfman was not only an amalgam of every border blaster archetype that had come before – combining the showmanship of the preachers and the salesmanship of the quacks with a little bit of beatnik – Wolfman truly had his finger on the pulse of the American teenager. Wolfman Jack became, in fact, the Cotton Mather of rock and roll.

Wolfman Jack became a sensation overnight. There has never been a more popular DJ before or since, and only the launch of MTV on August 1, 1981 generated the kind of excitement that rivaled Wolfman Jack’s arrival on the scene. But with that success came lots of money. And, given the sometimes sketchy nature of the radio business, much of the money came in the form of cash. Some of XERF’s former employees recalled advertisers showing up with thousands of dollars in cash for the Wolfman. And that money attracted bandits… and the Mexican government, which were often just bandits in three-piece suits. A group of bandits attacked XERF in late 1962, and one employee was killed. Another attack came in 1964; thankfully, no one was injured this time. The attacks caused Wolfman to hire his own security force, because even though he lived in Del Rio, he had to travel to Mexico to broadcast his show, thanks to the Brinkley Act.

As you might guess, the attacks gave the Wolfman even more publicity. The juggernaut that was Wolfman Jack only seemed to get more and more popular as his show stayed on the air. One thing would change, however: after the second attack, the Wolfman moved to XERB, another border blaster in Tijuana, easily heard in Los Angeles. It was this station that George Lucas immortalized in American Graffiti. Wolfman’s show had become too big for just one station, though. By the late 1960s, Wolfman was doing three daily shows on XERF, XERB, and XERG. His show could be heard all over the world – not just the US, Canada and Mexico, but sometimes Korea, Scotland and other parts of Europe, too, depending on the weather. His popularity just didn’t seem to wane – every time he went on the air, the number of listeners went through the roof and phone lines at XERF, XERB and XERG lit up.

For years, people begged the Wolfman to make appearances at movie premieres, TV talk shows, awards ceremonies, fairs, corporate retreats, and other venues. During that time, the Wolfman ignored their pleas, as he wanted to maintain the “mystery” of the Wolfman. In 1969, however, the Wolfman finally broke down and appeared in brief cameo in the sketch comedy film A Session with the Committee. In 1973, the Wolfman appeared in American Graffiti… and this proved to be his downfall.

For years, people had pictures in their minds of what the Wolfman looked like… and they were sorely disappointed by the average looking white guy they saw in the film. Radio itself was changing, too. Thanks to the Wolfman, many other “wacky” DJs had taken to the air, and thus, Wolfman’s shtick wasn’t unique any more. The Wolfman suddenly became a parody of himself, appearing on shows like The Odd Couple; What’s Happening!!; Vega$; Hollywood Squares; Married… with Children; and even Galactica 1980, one of the most hated shows in TV history. The Wolfman took the “Elvis path”, drowning himself in cheeseburgers, cigarettes and cocaine.

After falling ever deeper on the “D-List”, Wolfman enjoyed a brief renaissance in the mid 90s. He had a live weekly program and was on a book tour promoting his autobiography, Have Mercy!. On July 1, 1995, he entered his home in Belvidere, North Carolina after doing his live show in Washington, DC. He hugged his wife, said “Oh, it is so good to be home!”, and then died in her arms. He was 57.

XERF scraped by for a few years after the Wolfman left, playing the same mix of preachers and quacks that it had before Wolfman Jack. Eventually, however, AM radio would almost die.

Although FM radio had been invented in the 1930s, it wasn’t until the mid 1960s that stations began broadcasting in FM, which allowed for better sounding music and stereo broadcasts (the “AM stereo” standard, by contrast, wasn’t officially adopted in the United States until 1993). By 1978, the number of listeners of FM stations exceeded AM in the US for the first time, and for a while there were plans to abandon the AM band altogether and use the bandwidth for other purposes. In 1987, however, the FCC repealed the fairness doctrine (which had required stations to offer “equal time” to opposing political views). The doctrine’s repeal, along with the relatively cheap airtime on AM stations, led to the explosion on politically-oriented talk radio in the 1990s. So AM lives to broadcast another day.

It’s hard to imagine how American music would be without XERF and Wolfman Jack. At at time when America was divided by race and class, Wolfman brought everyone together and exposed the country to artists like The Supremes and James Brown. He also broke the mold of the “boring DJ” and made him as important as the music he played. Not only did the Wolfman have a unique “act” that entertained, he played any records he damn well pleased. There were no “corporate-approved playlists” back then. For a brief moment, when thousands of DJs emulated the Wolfman, American radio was a beautiful, anarchic place where anything could come over the airwaves at any moment. And it’s sad that that’s all gone now.

Before the internet, there was short wave and night time A.M. (medium wave) radio. Living in the middle of the United States, an important one for me was Jean Shepherd on WOR. But border blasters couldn’t be ignored.