Human beings have known about the uniqueness of fingerprints for a long time. Ancient Babylonians used fingerprints for signatures. The famous Code of Hammurabi (1700 BC) authorized authorities to record the fingerprints of those who were arrested. The ancient Egyptians, Minoans, Greeks and Chinese used fingerprints as a form of identification, usually on legal documents, but sometimes as a “maker’s mark” on pottery items. By 702 AD, the Japanese had adopted the Chinese fingerprint method to authenticate loans.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe seemed to forget about fingerprints for a long time. It wasn’t until 1684 that English physician Nehemiah Grew published the first scientific paper about fingerprints. Just over a century later, in 1788, German anatomist Johann Christoph Andreas Mayer published a paper in which it was recognized that each fingerprint is unique.

Fingerprinting got a big boost in 1858. And that’s because of Sir William James Herschel, grandson of William Herschel, the German-born English astronomer who discovered Uranus, and son of John Herschel, who named seven moons of Saturn and four moons of Uranus.

William James Herschel was an officer in the Indian Civil Service in Bengal. Herschel became a big proponent of fingerprinting after becoming fed up with the rampant forging of contracts and legal papers that was going on in India at the time. Herschel’s decision to require fingerprints on most legal documents not only made forging them much more difficult, it almost eliminated fraud in pensions, in which family members continued to cash checks long after their relative had died. This was, of course, costing the English authorities a massive sum of money. Shortly thereafter, Herschel also began fingerprinting prisoners as soon as they were sentenced, as it was somewhat common for Indians to pay someone else to serve their prison sentences.

In 1880, Dr Henry Faulds, a Scottish surgeon who had been appointed by the Church of Scotland to open a mission in Japan, published a paper in the journal Nature on how fingerprints were unique and could be used for identification purposes. Faulds’ interest in fingerprints came about thanks to an archaeological expedition he went on with an American friend, Edward S. Morse. Faulds noticed that he could see ancient fingerprints in recovered pottery shards, and he began looking at his own fingerprints. Shortly thereafter, the hospital Faulds founded was broken into. A staff member was accused of the crime, but Faulds was certain the employee was innocent. He compared fingerprints found at the scene with those of the suspect and found that they were different. This convinced Japanese police to release the man.

Faulds was busy in Japan. Not only did he introduce Joseph Lister’s antiseptic methods to Japanese doctors, he also created the first lifeguard stations, founded the “Rakuzenkai” (Japan’s first society for the blind) and stopped epidemics of rabies, cholera and the plague. He even found time to learn Japanese, write two books and several academic articles, and to start three magazines.

But things went downhill for him when he returned to the UK. He offered to share his fingerprint theories with London’s Metropolitan Police, but was turned away due to a lack of concrete statistical analysis. He then contacted Charles Darwin for help in the matter, but Darwin passed on it, citing his declining health. Darwin forwarded Faulds’ work to a relative, Francis Galton, who in turn forwarded it to the Anthropological Society of London… who did precisely nothing with it.

Galton would return to Faulds’ work eight years later, but by then Faulds was in a huge feud with Herschel. Herschel had read Faulds’ article in Nature and had wrote the journal to say that he had been using fingerprints for years. In 1894, an incredulous Faulds demanded that Herschel provide him with some sort of evidence of this, which Herschel then provided. The two argued over the matter for years, with Faulds insisting that he had been the first to “discover” fingerprints, and Herschel arguing that he had been cheated out of scientific credit. In the meantime, Galton, who’d ignored fingerprints for years, suddenly developed an obsession for them, and produced a solid statistical model which calculated the possibility of two people having the same prints at 1 in 64 billion.

In 1891, Juan Vucetich, a Croatian-born Argentine anthropologist and police official (how many of those do you think there were running around?) and Galton fan, began taking fingerprints of criminals and at crime scenes. In 1892 he got his first conviction, of a woman named Francisca Rojas who killed her two children and blamed it on intruders. Rojas is believed to be the first person ever convicted by fingerprint evidence. The Argentine police, impressed with Vucetich’s work, created the world’s first fingerprint bureau, and expanded the use of fingerprints throughout the nation. Other countries soon followed suit.

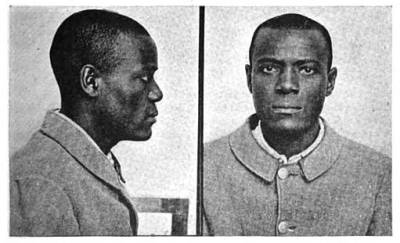

Except for the United States. Fingerprinting wouldn’t take off in the US until 1903, and that was due to one of the oddest events in criminal history. A man named William West was convicted of a crime and sent to Leavenworth Prison in Kansas. As part of the booking process, the prison clerk took West’s picture:

The prisoner looked familiar to the clerk, but West insisted that he’d never been in Leavenworth before. The clerk took West’s measurements and was even more convinced that he’d seen West before. He told West to stay put, and went looking through the records. He came back a couple minutes later with this:

Believe it or not, the man in the second picture is also named William West. Even though he looks remarkably like the first William West, and has the exact same basic body measurements, it’s not the same person. The second William West had been serving a life sentence in Leavenworth since 1901.

The “William West Incident” did more to force American authorities to adopt finger-printing than any other single thing. More than Herschel or Faulds’ work, or Galton’s statistical analysis, or Vucetich’s real world success. In 1906, New York City Police Department Deputy Commissioner Joseph A. Faurot introduced the routine fingerprinting of criminals to the United States.

,WOw!!..what a coincidence.!!

i like it.!!!